by Irina carnat

The news about the first “robot lawyer” defending someone in court sounded like the beginning of the end (of the legal profession, at least).

On 21 January 2023, Joshua Browder, the CEO of DoNotPay, a U.S. company based in San Francisco, California, providing – as stated in the latest Terms and Conditions updated 31 January 2023 – “a platform for legal information and self-help (whatever self-help means)”, that an AI would be arguing its first case in court. “A robot, in a suit, in a courtroom” was the first image to pop to mind. Of course, everyone freaked out, first and foremost legal professionals.

As a lawyer myself and a PhD student interested in the societal implications of Artificial Intelligence, I cannot help but wonder how unrealistic expectations – along with a general lack of understanding – around this technology might distort the reality. As the famous stoic Seneca once said, “We suffer more from our imagination than the reality”.

Spoiler alert: no AI is replacing lawyers (thank God, or the Constitution)! Leaving aside unrealistic expectations around Artificial Intelligence in the field of justice, it is time to debunk a few myths (and reassure a few thousand lawyers).

For this purpose, let us start by watching the interview broadcasted by NewsNation, available here: htps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2mY-3W256rY and take a critical view on the following statement:

“Robot-lawyer set to defend human in U.S. court”

Debunked myth #1: It’s not a robot, but an Artificial Intelligence computer app

The fact that it is not technically speaking a ‘robot’ allows us to better understand the technology behind DoNotPay’s services. It is an AI-driven application, fundamentally a chatbot, proving legal services. Simply put, it works by feeding a machine learning system with loads of documents and solved cases so that it can learn patterns and reproduce them in new cases. More specifically, as CEO Joshua Browder explains in an interview here https://donotpay.com/about/, it all started with parking tickets. The chatbot identifies the legal problem, find a loophole, turn it into a legal letter and send it to the right addressee. It basically automates certain tasks associated with the formal procedure for contesting a parking ticket. Since then, DoNotPay’s services broadened to, allegedly, over 200 areas of law, including hotel bookings, flight cancelations, even asylum seeking, and it even provides templates for legal documents and filings.

Having cleared that it is (not a robot, but) a chatbot providing certain legal services upon an annual subscription fee, let us move to myth number 2.

Debunked myth #2: It’s not a lawyer, but at most a chatbot providing legal advice

The mere statement that its AI is set to ‘defend’ someone in court in an actual case, as an attorney would do, is misleading, if not wrong altogether. It conveys the idea that AI might replace the lawyer’s defense in a courtroom, but this is not the case because you cannot replace the lawyer if there is no lawyer to replace in the first place. For non-legal experts, this might require a few words of explanation.

In certain small cases, such as traffic ticket although argued in court, you don’t need a lawyer to defend yourself [1]. These are low-stake scenarios, consisting mostly in infractions and not serious crimes, where you get fines and do not risk going to jail. It is clear thus you may hire to an attorney, a legal expert, or even a paralegal to prepare your arguments, which might guarantee you higher chances of success, but it is not mandatory, as you may even defend yourself if you can make your own convincing arguments.

On the contrary, in other high-stake scenarios, i.e. in crimes and misdemeanors, the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to counsel in criminal cases. This means that if a person is facing charges that could result in imprisonment, they have the right to an attorney. In many cases, if a defendant cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for them by the court.

It is clear at this point that the two cases (speeding tickets) chosen by DoNotPay to argue in court did not – technically speaking – require a lawyer to the argued in court. It follows that, at least in this case, the AI-driven app could not be regarded as – again, technically speaking – a lawyer. Therefore, the “robot-lawyer” cannot bill its hours, so DoNotPay them!

Debunked myth #3: It’s not set to defend a human in U.S. court, but… no, actually, that’s it: it simply cannot do that.I will be quick on this one.

The idea was to run DoNotPay’s app on the defendant’s smartphone so that it could listen to the court’s arguments in real time and thus whisper the appropriate defense via earpiece. This would constitute use of hearing aids, but since DoNotPay’s technology would also require recording the events happening in the courtroom, this might be illegal in many courtrooms.

Against the initial enthusiasm of having found, despite evident struggle, two out of three hundred cases where DoNotPay could be deployed, the State Bar prosecutors definitely barred the possibility for the “the first robot lawyer” to argue in court. [2]

“It’s in the letter, but not in the spirit of law”. I believe there is not much to be added here. And this likely explains the recently revised Terms of Service on 31 January 2023, clarifying that DoNotPay is not a law firm, and that the information provided by DoNotPay along with the content on our website related to legal matters does not constitute [legal] advice. https://donotpay.com/learn/terms-of-service-and-privacy-policy/

Having debunked the myth of AI taking over the legal profession, a few considerations are nonetheless worth mentioning from the interview above. In fact, at 2:14 of the video, the interviewer raised perhaps the most important issue of all, that will be briefly discussed here in three points:

- The lawyer’s billable hours: what do we pay for exactly?

Beside the cost of law school tuition, which in the U.S. can amount to an average of $84,558 at public universities for in-state students, and $147,936 for students that attend private universities [3], lawyers undergo a thorough training that culminates in taking the bar exam in order to be licensed to practice law in a specific jurisdiction: it is typically administered by the state in which the lawyer seeks to practice and is designed to assess the candidate’s knowledge of the law and their ability to apply it to real-world situations. By passing the bar exam, the candidate demonstrates their competence and commitment to the legal profession and shows that they have the skills and knowledge necessary to represent clients effectively. As such, the lawyer’s job is not merely that of copy-pasting briefs and documents, but formulate the adequate defense based on the specific clients’ needs, which entails deep knowledge of the legal system and its principles. This task that cannot be easily automated or delegated to an AI system, and for this reason, (at least some of the) counseling services provided by legal professionals are worth the bill.

- Access to justice: is it just about the costs?

The problem with access to justice is indeed a pressing issue, but not necessarily for the reasons mentioned in the interview. In fact, one aspect is money and the other is time [4]. Having unfolded and partially justified lawyers for being so expensive due to their intense training and preparation to be able to perform one the fundamental role within a democratic society, i.e. justice, access to (real) justice may be hindered by extremely and sometimes unnecessarily lengthy processes to achieve a legally binding decision. The reasons behind this phenomenon, such as courts’ work overload, lack of personnel etc., would go beyond the scope of this analysis, but it is worth considering the issue from a different perspective. Advancements in computational capabilities, along with widespread collection of data and their analysis, impact – in a beneficial way – a wide range of societal sectors. Just consider AI and its analytical and predicting capabilities: should justice and legal services in general be excluded altogether because of the high risk on the interests at stake, or should we try and consider that – at some point of the societal progress – change is inevitable, and in some cases, even desirable?

- Law stake cases vs fundamental rights: who is responsible?

Assuming that the deployment of AI in the judicial field is inevitable and to some extent even desirable, the most critical concern is how to guide this process of integration of such a disruptive technology into a field that heavily relies on human decision-making. It ultimately boils down a very simple, yet fundamental, concept: responsibility.

Sure, we all have in mind the famous quote “With great power comes great responsibility” (yes, commonly attributed to Uncle Ben, but it has a much richer history [5]), but in the judicial decision-making process responsibility is a directly proportionate to the interests at stake. For this reason, the higher the stakes, the higher the responsibility of adopting the appropriate procedural safeguards imposed at constitutional level. Indeed, small consumer cases could be handled differently than criminal cases, where not only economic interests, but fundamental rights are at stake.

Back to DoNotPay: their mission is “to help consumers fight against large corporations and solve their problems like beating parking tickets, appealing bank fees, and suing robocallers, to level the playing field and make legal information and self-help accessible to everyone.” [visit their website https://donotpay.com/about/]. This is a very noble goal that cannot but get our sympathy. However, if this phenomenon of AI-powered tools might teach us something is that justice is complex, time-consuming, and expensive and we might as well use technology to make it more accessible, as long as the appropriate safeguards are put into place.

At 3:25, Browder said: “I wouldn’t want to be a lawyer charging hundreds of dollars to copy and paste documents.” Dear Joshua, believe me, as a lawyer, I wouldn’t want that either. But it is not the “charging hundreds of dollars” (for the considerations above, there is a sound reason why lawyers are expensive, and rightly so): the problem is the copy-pasting activity that can – and should, with the appropriate safeguards – be automated if the technology provides the means.

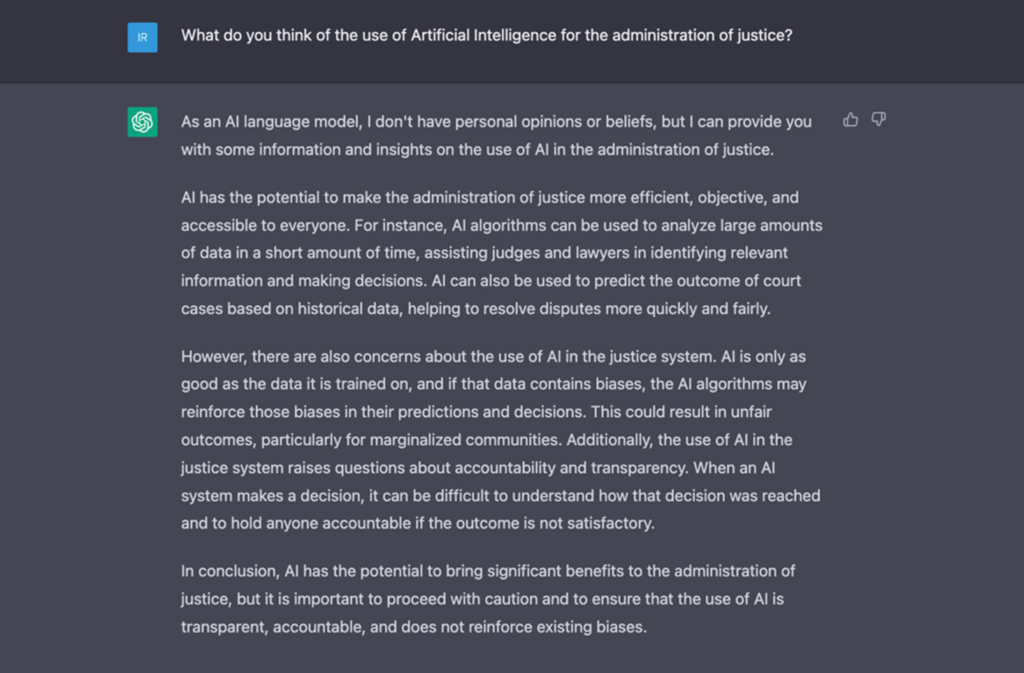

To draw a conclusion, I asked the “legal expert” ChatGPT, that have recently passed the Bar Exam [6] (congratulations!), but wants to remain humble about it, what it thinks of the use of AI in the field of justice. This was the response:

“I think there have to be rules”. Here again, I must agree with Joshua. As long as companies like DoNotPay use AI-driven apps to help consumers through unduly complex bureaucracy of small claims, and thus favoring to some extent access to justice, their activities should not be discouraged, but regulated instead. The first step should be to hold these companies accountable for the performance of their AI-driven app and requiring a certain degree of transparency and auditing. On the other hand, if these companies were to use AI as a cheaper solution to expensive legal counseling, such as defending someone in court, the preliminary step would be to ask if and how they are willing to take on the responsibility, or burden, of performing one of the fundamental functions of a democratic society, which is justice.

The paradox here is clear: this is not a question they can answer because assigning responsibility for justice to an AI is out of the question.

Law is complex, and justice is a serious matter: DoNotPLay around with it.

Stay tuned!

Irina Carnat,

PhD student and researcher in Artificial Intelligence for Society at Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna and University of Pisa.